#DivineTheft

Trespassing Above and Below

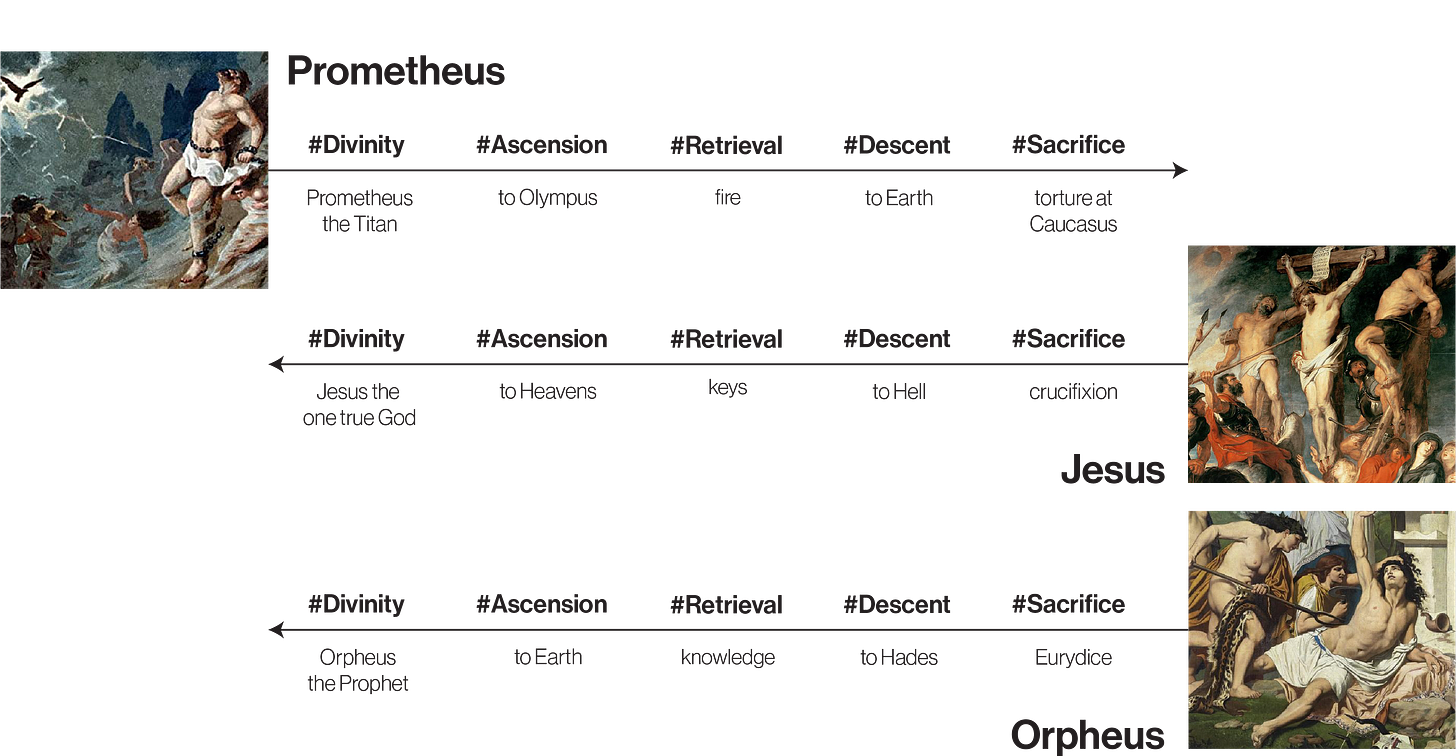

I. Stealing from the Heavens

Prometheus at once went to Athene, with a plea for a backstairs admittance to Olympus, and this she granted. On his arrival, he lighted a torch at the fiery chariot of the Sun and presently broke from it a fragment of glowing charcoal, which he thrust into the pithy hollow of a giant fennel-stalk. Then, extinguishing his torch, he stole away undiscovered, and gave fire to mankind.

Robert Graves, The Greek Myths: Vol. 1 (1955)

Prometheus, a persona non grata in Olympus after deceiving Zeus in what came to be known as the Trick at Mecone, took pity on the suffering of mankind. Deprived of fire, people were condemned to eat raw meat and bear the cold of night. Upon discovering that Prometheus had trespassed into the heavens and gifted the contraband fire back to the humans, Zeus ―enraged once again―, bound him to the Caucasus Mountains as punishment, setting a giant eagle to pierce his immortal skin and devour his regenerating liver every day.

II. Stealing from the Underworld

When I saw him, I fell at his feet as though dead. Then he placed his right hand on me and said: "Do not be afraid. I am the First and the Last. I am the Living One; I was dead, and now look, I am alive for ever and ever! And I hold the keys of death and Hades.

Book of Revelation, 1:17-18

A Promethean figure in his own right, Jesus presents the previous myth’s mirror image. After being bound to a cross and pierced on his side ―right where his liver would be―, Jesus descended to the underworld where he preached to the antediluvian souls and took with him the keys to the Doors of Death. He returned, triumphant, to the world of the living, before reclaiming his position as a god in the heavens.

III. Stealing from the Underworld (reprised)

Our next prophet, Orpheus, also tried to retrieve something from the underworld that wasn’t his. Like Pirithous after him, he descended to Hades to find his bride, Eurydice, who had been killed by a viper’s bite while escaping the lustful chase of a satyr, or the bee-keeper Aristaeus. Eurydice’s name ―meaning “profound judgement”― would be premonitory of the tests that Orpheus would face during this dark journey. As the greatest of all poets and musicians, Orpheus’ songs soothed the gatekeepers of hell: the three-headed hound Cerberus, the three Judges of the Dead, and ultimately Persephone and Hades themselves, who agreed to release Eurydice under one condition: Orpheus must exit the underworld without looking back, and only outside, could he reclaim his beloved Eurydice just behind him.

In line with my cyclical reading of myths, this condition is set in place to be inevitably broken. So like Edith looking back at Sodom, Orpheus turned his head too soon at the end of his journey, only to see the silent Eurydice pulled back into the shadows of the underworld, now lost forever. His intended mission failed.

Or did it?

Plato says that Orpheus’ test was a fool’s errand; that he really didn’t have a choice to recover his bride because the Eurydice that followed him was a decoy. The gods, in their infinite wisdom, knew that Orpheus would fail and were punishing him for his cowardice at wanting his wife to come back to life, rather than wanting himself to be dead to join her.

And yet, the most common retelling of the story is the one framed as a cautionary tale where “curiosity killed the cat”, used to teach children why they shouldn’t fail their Marshmallow experiments. This might seem alluring for a Scholastic Book Fair, but remains unconvincing to adults like Plato. As anyone who has ever loved another can assert, one does not gamble the loss of true love over a few seconds’ impatience.

Regardless of what happened in that last stretch of Orpheus’ journey, he failed to steal Eurydice back from Hades ―but he did not leave empty-handed. While there is no clear reference as to when Orpheus is initiated into the Sacred Mysteries that bear his name, we do know that his travels to the underworld echo the foundation of his Order, wherein Eurydice ―sorry, Eros―, the hermaphrodite spawn of the chthonic Moon Goddess and primeval incarnation of love and desire, is the prime mover of the Universe.

As Orpheus exits Hades, he carried with him the newfound truth of the world’s cosmogenesis, a burden of knowledge that left no place for the idyllic life he had envisioned with Eurydice. He entered Hell as a mortal, but left it as an initiate who understood that his mission in life was now to initiate others: to preach that there is only one god which is the Sun, to renounce heterosexual love, and to prophesize the future, even at the expense of knowing that his fate was to get ripped to shreds by his own followers, the Maenads. Orpheus knew that even death would not keep his lyre from playing or his severed head from singing as it floated down the River Hebrus into the sea. He knew that the Orphic Mysteries were now his to carry, and that this calling left no place for his beloved Eurydice, his “profound judgement”.

The same love that created the Universe still flowed through Orpheus’ veins for Eurydice, and so he walked out of Hades with parsimony, delaying the inevitable, waiting for the last minute ―nay, the last second―to make the choice he knew he had to make and send Eurydice back into the darkness, so that he could be reborn under the light of the Sun as the prophet he was always meant to be.

Coming up next. I’ll continue the deep dive into the myth of Orpheus and the trope of #TalkingHeads.

And a fun fact. Prometheus’ punishment also marks the earliest disinformation campaign I have found in mythology. To hide his vindictiveness towards Prometheus for having given fire to mankind, Zeus claims that his actions were a punishment for a tryst with the virginal Athene ―Zeus’ own daughter―, who had conspired with him in the theft. Truly, Dad of the Year.